Richard Frame and John Frost's Grave Stone

Richard Frame and John Frost's Grave Stone

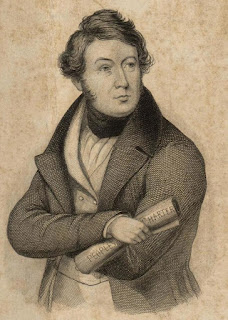

On Richard Frame's regular trips to Newport Museum and Art gallery he would always pause at the cabinet that housed the Chartist Collection. It included a photograph of John Frost’s house in Stapleton, near Bristol, where he went to live with his wife and daughter when he was finally allowed to return to Britain in 1856.

John Frost was born on 25th May 25 1784, in Newport, Monmouthshire, and died on 27 July 1877, near Bristol. He was a hero of Chartism which was the first mass political reform movement and was leader of the Newport rising of November 4, 1839, in which about 20 Chartists were killed by troops. He was a prosperous draper and tailor in Newport and served as a member of Newport’s first elected town council from 1835, and as a magistrate from 1836–39 and mayor from 1836–37. He was a delegate from Monmouthshire to the Chartist convention in London between February to September 1839 and occasionally was convention chairman, in which capacity his tie-breaking vote dissolved the assembly. Returning to Newport, he became involved in militant Chartist activities that culminated in the street battle on November 4.

Since 1983 Richard Frame had been

living on Bassaleg Road and had taken an interest in locating those people

buried in St Woolos Cemetery who had played a role in the development of the

town. It wasn’t just those who had grand memorials to keep their names alive as he was equally interested in the dips in the ground which were the resting place of those unknown souls who had also played their part in Newport's history. This meant long periods thumbing through old

newspapers in Newport Reference Library and seeking out their stories.

It occurred to Richard that he didn’t know where John Frost was buried. He wondered if the body was brought back to Newport after his death in 1877 or whether it was put to rest near Bristol? It soon became apparent that no one had any idea where his body lay. Therefore in 1986 together with a friend, Derek Priest, Richard made a visit to Stapleton to search out any local burial grounds that might reveal Frost’s resting place, but that came to nothing. Bristol’s Reference Library provided no clues and a visit to Canford Cemetery in Bristol, where they held the records of all those buried in public cemeteries, revealed nothing.

The answer was eventually uncovered in Newport’s Reference Library. In a document published in 1939 to commemorate the centenary of the Chartist Rising there were lists with descriptions of all the documentation they held in their collection, There on the first page was what he was seeking, a copy of Frost’s will dated 12th June 1874. Here was the following sentence, “I desire that my funeral be a public one and that I be buried by the side of my wife and son in Horfield Churchyard”. The burial records housed in the Bristol’s reference library confirmed that John Frost was indeed buried in Horfield Churchyard. As it was a small burial ground he was convinced that he would locate it easily, but after two hours of looking at every stone, he drew a blank. A further two hour search revealed nothing.

Richard and his friend Derek had come so close to finding the grave. Calling at the vicarage to say goodbye to Canon Wilson, they found him clutching a small notebook. He explained that in 1946 a church warden had recorded all the names from the stones and had even drawn a location plan. He had looked through the note book, but could not find a John Frost. However, there was a Henry Hunt Frost. Richard knew that he was the son of John Frost named after the famous orator at the Peterloo Massacre. On the north eastern side of the church close to the boundary wall, they found a small stone that looked as if it was sinking into the ground. All that was readable was the following, “Sacred to the memory of Henry Hunt…” Feeling around in the grass Richard found the bits of flaked stone that revealed the word “Frost”.

Newport Council

agreed to pay for a new headstone, and stonemasons Les Thomas and Brian Jarvis

set to work by firstly removing the old stone which had almost disappeared. Unfortunately it proved too difficult to lift out the whole stone, so it was reluctantly agreed to cut it off just below ground level. Wrapped in sack

cloth, it was carefully removed to the safety of Les Thomas’ dusty work shop in

Baneswell in Newport.

The New Gravestone

It was agreed that the

new stone should be slate with a granite surround and that it was to be of

Welsh stone. A trip to Carmarthen provided the slate and Les was able to

root out enough Welsh granite from his yard.The stone would include the Newport

coat of arms and the names of all those buried there and a short extract from

the text of a letter Frost had sent to Lord Tredegar: “The outward mark of

respect paid to men merely because they are rich and powerful… hath no

communication with the heart”.

Richard Frame and Alexander Cordell visit the grave.

On Thursday 9th October

1986 around 100 people gathered around the stone which was draped in a Welsh

flag, and before unveiling it Neil Kinnock MP, the leader of the Labour Party,

addressed the audience, concluding that “Whenever John Frost was faced with the

choice between that which was right and that which was safe, he always chose

that which was right”.

But back to the head stone. For a couple of

years the stone remained wrapped up in the stonemason’s work shop, but in 1990 Richard Frame took possession of it. Eventually, not being sure what to do with it, he lent

it to Russell Rees in Caerleon who had planned on putting it on show in the

Ffwrwm Arts Centre which he managed. But Russell passed away and it wasn’t until

October 2020 that Richard was reminded about it. He found Russell Rees's daughter working

in the Arts Centre that very morning, and later that day it was dropped off at Richard's home in Baneswell.

The gravestone of Chartist leader, John Frost has now been placed in the care of Newport Museum and Art Gallery. Carved from sandstone, it is in a fragile condition with parts of the remaining lettering flaking off. Funded by the Friends of Newport Museum and Art Gallery, stone conservator - Kieran Elliot was commissioned to clean and stabilise the gravestone. It took place in the Unit housing the Newport Ship where there was space for the restoration.

The gravestone of Chartist leader, John Frost has now been placed in the care of Newport Museum and Art Gallery. Carved from sandstone, it is in a fragile condition with parts of the remaining lettering flaking off. Funded by the Friends of Newport Museum and Art Gallery, stone conservator - Kieran Elliot was commissioned to clean and stabilise the gravestone. It took place in the Unit housing the Newport Ship where there was space for the restoration. The visit by a Newport group to John Frost's grave in October.

On Saturday 23rd October a group of Newport people went to see Newport County play Bristol Rovers and also went to see John Frost’s grave in Horfield Church yard. Since well before the 1839 Rising at the Westgate the friendship between working class movements in Bristol and Newport have flourished. Henry Vincent founded a radical newspaper called the Western Vindicator, printed in Bristol, that covered south Wales and the West country. The tradition stayed strong in both cities and current Bristol radicals are regular speakers at the annual Newport Chartist Convention held every year.

Presumably his son was named after the orator Henry Hunt, who was addressing the crowd at Peterloo in 1819 when the troops opened fire.

ReplyDeleteYes Linda that is correct.

Delete